The San Francisco Symphony presented an extraordinary concert at Davies Symphony Hall, October 3-5. Is it possible that music lovers love to critique the music that we love? Maybe it is just Opera fans who talk about old war horses. The program sizzled opening with a new piece by Timothy Higgins, Principal Trombone in the SFS since 2008. He has left the SFS to become the Principal Trombone in the Chicago Symphony.

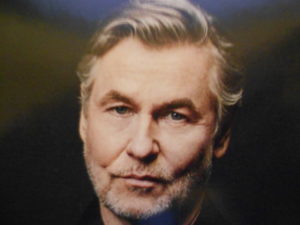

Market Street, 1920s, had its world premiere this weekend. It has two elements for the music. Higgins described the tone of the music fitting the black and white pictures of SF streets with cars traveling around Market Street. There is also an argument. Two individuals take up opposite sides in SF’s issues, especially about alcohol. SF police, it is said, were told to look away from speakeasies and bootleggers. San Francisco’s history includes resistance to the federal government’s decisions. The music also represents “academic” leaning music and the more popular. There are jazz passages that give the music a rhythmic kick. There is no solution to these arguments. Sometime arguing is an athletic sport. This eight minute piece was a happy introduction to the evening. Well done, Tim Higgins. Photo: Tim Higgins talks about his premiere work.

The San Francisco Symphony with Gustavo Gimeno, conductor, and Javier Perianes, piano, perform Timothy Higgins’ “Market Street, 1920s” a SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere, Edvard Grieg’s “Piano Concerto,” and Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “Symphony No.5.” At Davies Symphony Hall on Friday night, October 3, 2025.Photo by Stefan Cohen

Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907) He composed his magnificent Piano Concerto in A minor, Opus 16, in 1868. The first time I heard it, I was surprised that it was Grieg’s work. I had heard his music that was influenced by Norwegian folk music. This is something completely different. It is a wonderful Concerto. The opening of the music, Allegro molto moderato, seems so natural that every note is where it has to be. It shows its lyrical side as well as the strength of the music in its cadenza. The second movement, Adagio, has amazing delicacy. The notes have no weight. I hear them as though it is gentle snow falling. No clumps, no ice, just the lovely snow flakes. I know they are each made of unique designs even though I cannot see their always different presence. The final movement, Allegro moderato molto e marcato, is also something unusual but perfectly the right music. Grieg’s interest in Norwegian folk music shows its character. The movement has the music equivalent of a play within a play. The movement creates another concerto within this movement. Grieg plays on with another cadenza and a false exit. Very new and something to surprise one’s ears. The rest of this mini-me concerto begins slowly, but Grieg has other directions to fulfill this brilliant concert: lots of violins and trumpets. The musical marriage made with two so unlike instruments lifts the concerto and thrills the audience. The soloist was Javier Perianes. He has performed in most venues you can think of around the world. He records for Harmonia Mundi. His performance was exactly right just as every note was the right note. Perianes treated Grieg right just as he deserved. Pianist Javier Perianes photo below. Photo by Stefan Cohen

The San Francisco Symphony with Gustavo Gimeno, conductor, and Javier Perianes, piano, perform Timothy Higgins’ “Market Street, 1920s” a SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere, Edvard Grieg’s “Piano Concerto,” and Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “Symphony No.5.” At Davies Symphony Hall on Friday night, October 3, 2025.

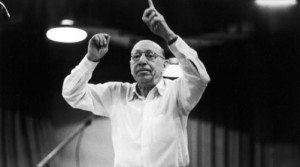

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) The Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64, was created in 1888. This has been a beloved, moving symphony since it premiered. In the 1890s, it was attacked for being “ultra-modern” and even for Tchaikovsky’s ancestry. “while in the last movement, the composer’s Calmuck blood got the better of him, and slaughter, dire and bloody swept across the storm-driven score.” Tchaikovsky was not related to this ethnic group in Russia which was actually Buddhist. Fortunately, the composer overcame a depressive attitude toward the 5th Symphony which he had loved as much as its audiences loved it. There are several themes that appear more than once throughout the symphony. It begins with Andante-allegro con anima. It seems to be dark with its clarinets, but Tchaikovsky lets a lovely waltz interrupt the unhappy theme. The end of the first movement has a rough feeling. Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza, the second movement, truly moves onward with a charming attitude, but the theme in the first movement invades the second movement. The third movement, Valse: Allegro moderato, dances its way to sunshine and no dark clouds. The signal for the end is the theme from the first movement moving into the springy waltz. The closing movement seems to know how to tame the first movement’s theme. It takes away its threatening just when the finale begins a march rhythm that sets the music into a serious drama. The ending is triumphant. It is a sunny day. Photo below Conductor Gustavo Gimeno, photo by Stefan Cohen

The San Francisco Symphony with Gustavo Gimeno, conductor, and Javier Perianes, piano, perform Timothy Higgins’ “Market Street, 1920s” a SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere, Edvard Grieg’s “Piano Concerto,” and Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “Symphony No.5.” At Davies Symphony Hall on Friday night, October 3, 2025.

Conductor Gustavo Gimeno led the orchestra to a great performance. He has a graceful way of conducting and is totally in the music. His presence in the music also helped produce excellent performances by all the musicians with solos or featuring of their sections. It was a magnificent evening.

Magnus Lind

Magnus Lind Alban

Alban

Ralph Vaughn Williams, composer (1872 – 1858), England

Ralph Vaughn Williams, composer (1872 – 1858), England

Anna Thorval

Anna Thorval Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957), Finland

Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957), Finland

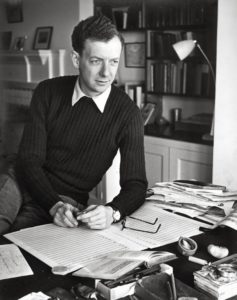

Benjamin Britten

Benjamin Britten Sasha Cooke, mezzo soprano

Sasha Cooke, mezzo soprano

Shostakovich at the piano

Shostakovich at the piano Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony

Einojuhani Rautavaara, compo

Einojuhani Rautavaara, compo Paavo Jarvi

Paavo Jarvi Kirill Gerstein, pianist

Kirill Gerstein, pianist Gustav Mahler, composer (1860

Gustav Mahler, composer (1860

Missy Mazzol

Missy Mazzol

Sa

Sa