The San Francisco Opera presented the premiere of The Monkey King opera. It is a strange kind of premiere since the novel which it is based on, Journey to the West, was written in 1592 and has thrilled audiences ever since then. It is considered among the four most important Chinese classics. It is a story with wars, humor, singing, dancing, martial arts, and, of course, flying. The creative team includes: Huang Ruo, music; David Henry Hwang, libretto; Conductor, Carolyn Kuan; Director, Diana Paulus; Choreography, Ann Yee; Puppets & Sets, Basil Twist; Lighting Design, Ayumu “Poe”Saegusa; Costume Design, Anita Yavich.

Cast of the Monkey King

Cast of the Monkey King

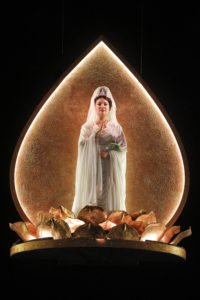

The opera opens with Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, chanting Buddhist prayers. She knows that Monkey has been locked up in a cave for 500 years. When the audience sees Monkey for the first time, he is angry and fed up, especially because he does not have much more than trash to eat. Mei Gui Zhang was a beautiful Guanyin. Her posture and stage presence make her seem to float. Her voice was calming and soars without pushing to the notes. She expresses mercy through the music. The Monkey gets out of his cave and a mass of monkeys decide to follow him and make him King. Monkey wants to find the secret of eternal life to protect his children from death. Kang Wang as the Monkey King was perfect. He was able to project all the emotions he feels when he is up against the Jade Emperor. Konu Kim was appropriately wicked, scary, and hangs out with the other crooked rulers. When Monkey gets to Heaven, he sees that the gods are corrupt and very mean. One suggests that The Monkey King should be bar-be-qued, but The Monkey King comes out of the oven bright eyed and powerful.

Mei Gui Zhang, Guanyin; she is suspended above the stage.

Mei Gui Zhang, Guanyin; she is suspended above the stage.

There are additional Monkey Kings. There is a Monkey King Dancer, Huiwang Zhang; Lord Erlong Dancer, who knows how to fight the King and a puppet Monkey King. It makes sense to have the cast represent all aspects of the Monkey King. Their talents express the fullness of the King. This opera has an overwhelming, active, gorgeous production.  This is the Dragon Palace of the Eastern Sea; making a scene under water is a fabulous event.

This is the Dragon Palace of the Eastern Sea; making a scene under water is a fabulous event.

Early in the first act, The Monkey King finds a master to teach him.The teacher gives him a new name, Sun Wukong. Jusung Gabriel Park, was both the teacher, Subhuti, and Buddha. He has to have Buddha’s patience to teach the Monkey. The Monkey did not realize that his teacher was Buddha. As the Monkey wins most of his battles, he feels powerful. However, his teacher warns Monkey: Power is not enough.

The Five Element Mountain.

The Five Element Mountain.

Monkey has misbehaved in a very big way. He has no humility and does not care about the suffering of others. Guanyin reminds him that he heard the teacher but did not listen. Buddha challenges Monkey to jump out of Buddha’s palm. Monkey was sure that it would be simple to do since he has escaped and fought in so many situations, but he is wrong. The Five Elements Mountain was Buddha’s hand. Monkey joins the followers of Buddha and goes forth with his spirit to help all beings reach the Land of Bliss.

Only thing wrong with this opera: I want to tell my friends in Chicago and St. Louis and Portland to go to see it, and it is not available. Not yet. I must learn patience.

Photos by Cory Weaver; Thanks to the San Francisco Opera.

Itzhak Perlman

Itzhak Perlman

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-18

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-18

Richard Strauss, composer (1864 – 1949

Richard Strauss, composer (1864 – 1949