These two musical artists lit up Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, February 13. The program featured Debussy’s three works of Images pour orchestre, Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, and the SF premiere of Einojuhani Rautavaara’s Piano Concerto No. 1, Opus 45. Wang performed both concerti with power and her intimate knowledge of playing the piano. This program appears four times; it demands strength and excellence. Maestro Salonen, leading the SF Symphony, provides all the necessities brilliantly. There are two more performances: Tonight, Saturday, Feb. 15, 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, Feb. 16, 2:00. These are wonderful concerts with thrilling music and artists.

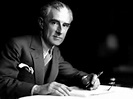

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony

Debussy’s Images pour orchestre are three separate pieces that Debussy created from 1905-1912. They are presented in varying order. This program opened with Gigues from Images pour orchestre (1912) followed by Rondes de printemps (1905). Ronde was the first part he created; it suggested the idea of the parts. The third part, Iberia, closed the whole program. Each piece is inspired by Debussy’s idea of three countries: England for Gigues, inspired in part by a folk song, “The Keel Row;” France for Ronde de printemps; Iberia for Spain. Gigues and Ronde were fascinating. Each is eight minutes. The title, Images, fits because Debussy was very taken by the French Impressionist painters. His work also is engaged in aural suggestions of Pierrot, the theater’s sad clown. The Images may recall characteristics of these countries, but these works are imaginative and circulate one’s experiences and memories. I would hear and see them again right now if I could.

The Piano Concerto in D major for the Left Hand, was composed by Maurice Ravel, 1929-30, specifically for Paul Wittgenstein. Ravel entered World War I hoping to be a pilot, but due to his age and health, he was a supply driver. Pianist Paul Wittgenstein had recently made his solo debut before the war. He had been “called up” by the Austro-Hungarian Army and scouted Russian positions. He was shot in his elbow; doctors amputated his right hand. While in the hospital, the Russians raided the hospital and took everyone there as a prisoner of war. He was sent on the long journey to Omsk, Siberia where there was a POW hospital. He began to try to re-train the fingers of his left hand by drawing a keyboard to drill his fingers. He was moved to a hotel that had an upright piano, but luck changed. He was moved to a horrible place in the gulag. It was so terrible that Dostoevsky made it the scene for his novel, The House of the Dead. Wittgestein was in a prisoner exchange that took him back to Vienna.

Maurice Ravel, composer (1875-1937)

Maurice Ravel, composer (1875-1937)

Wittgestein commissioned Ravel for a Concerto, but Wittgenstein “had issues” about the finished piece. After lengthy disputes, Wittgen stein finally recognized Ravel had composed a great work. Yuja Wang played brilliantly. One could see the physical challenge of the music. Yuja Wang balanced herself by having her right hand hold on to the right side of the bench and also by grasping the piano’s top. The Concerto is very athletic for the pianist. Ravel said, “even a single hand can create layers of sound and both melody and accompaniment at the same time.” Ravel was a jazz fan, and this Concerto shows his understanding of Jazz sounds and rhythms. He said, “After a first part in {a} traditional style, a sudden change occurs and the jazz music begins. Only later does it become evident that this jazz music is really built on the same theme as the opening part.” Wittgenstein, realizing his good fortune to have this Concerto in his repertory, played it in concerts everywhere, including with the San Francisco Symphony, 1946. Watching Yuja Wang play this makes one realize the physicality needed to make music. She is ready for Olympic gold. Fascinating to watch, and listening to her playing in person is a great reward for the audience.

Einojuhani Rautavaara, composer (1928-2016)

Einojuhani Rautavaara, composer (1928-2016)

Rautavaara was the most famous Finnish composer when he passed away relatively recently. He studied at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. He said that he was not a piano prodigy, but “with no personal contact with music as yet, I painted ‘music’ on paper in watercolors.” He received a master’s degree from the Academy and Sibelius chose him to win the study grant honoring Sibelius’ 90th birthday. He used the grant to study with Roger Sessions and Aaron Copland, in 1955 and 1956. He continued studies at Julliard and in Europe. He was interested in all the serious music trends, including 12 tone serialism. He composed eight symphonies and forty other orchestral works. His Piano Concerto No. 1, Opus 45 (1969) opened his eyes to alternatives to the most fashionable styles. He leaned into neo-Romanticism in his own style. “I was disappointed…with the then fashionable ‘ascetic’ –and to my mind anemic –piano style, and i wanted in my concerto to restore the entire rich grandeur of the instrument, to write a concerto ‘in the grand style.'” Yuja Wang was the right person to present the grand style. The Concerto needs a strong technique and deep understanding of the music. There were many physical performance requirements. The pianist had to use her whole lower arm to make the sound of all those notes at the same time. Her hands had to jump over each other. It was a powerful Concerto with a powerful artist bringing it to an excited audience. Yuja Wang was cheered into encores: Etude No. 6, by Philip Glass. The audience went wild again. The second encore was Danzon No. 2, by Arturo Marquez. Ms Wang is a great personality in addition to a fabulous performer.

Music Director Salonen closed this wonderful program with SF Symphony playing Debussy’s third part of the Images pour orchestre, iberia. The impressionistic music wafted around the hall. It has Spain’s light, colors, an atmosphere of people dancing a sevillana in the town’s plaza. The music suggests visual experience in the music. The scent of a place Debussy had never seen surrounded us in his imagination.

Note: Quotations of Ravel are from Benjamin Pesetsky article SF Symphony program. Quotation from Rautavaara are from James M. Keller article in SF Symphony program.

Hector Berlioz (1801-1869) French

Hector Berlioz (1801-1869) French

Photograph courtesy of the website of artist/animator Gregoire Pont from the premiere of L’enfant et les Sortileges, Lyon, France, 2016.

Photograph courtesy of the website of artist/animator Gregoire Pont from the premiere of L’enfant et les Sortileges, Lyon, France, 2016. Fire in L’Enfant et les Sortileges

Fire in L’Enfant et les Sortileges