You may have seen Frankenstein movies; the Frankenstein ballet is better. Nothing against Boris Karloff, the Monster (or Creature); he was so good in the 1931 movie that the story goes on and on. Before I tell readers more, I advise you to get tickets now. Frankenstein’s last day and night is May 4th. Week day tickets are available now at half price.

Go to this link: https://www.sfballet.org/productions/frankenstein-encore/

The most important aspects of this ballet are the wonderful performances. I saw it with Dores Andre as Elizabeth Lavenza, Victor’s fiancee; Max Cauthorn as Victor Frankenstein, the aspiring scientist; Nathaniel Remez as The Creature; Alexis Francisco Valdes as Henry Clerval, Victor’s best friend; Julia Rowe as Justine Moritz, when Victor and Elizabeth were young, Justine was a playful friend, but she had a tragic future. The entire company danced so well it is difficult to describe the feats they achieved. They had intensity as well as technique; theater skills that lifted them out of any staginess; lifts and jumps that were real though they seem unreal.

Jasmine Jimison as Elizabeth & Cavan Conley as The Creature, FRANKENSTEIN ballet by Liam Scarlett performed by SF Ballet, photo Lindsey Rallo

Jasmine Jimison as Elizabeth & Cavan Conley as The Creature, FRANKENSTEIN ballet by Liam Scarlett performed by SF Ballet, photo Lindsey Rallo

The choreographer of all this, Liam Scarlett, devised a way for a lift to go higher. The ballerina is lifted by the danseur; he catches her up from a jump; she makes a second jump into the air from his arms. I write that it is a second jump, but to jump one normally pushes off from the floor – or from something. Here, the ballerina engages her energy and ascends. Does the partner toss her up again? Maybe. Ballerinas are strong and equally brave as they are strong. That’s it.

The ballet has two amazing pas de deux for the leads. They dance together when they decide they will marry. It was lovely and did not hide their emotions. The elegant turning into each other and sometimes away from each other was continually inventive and beautifully executed.

Another pas de deux happens when Victor has lost The Creature. He is anxious and preoccupied. Elizabeth tries to calm him with some of the steps from their previous pas de deux, but they cannot get back to the Before The Creature feelings.

There are choreographic motivations demonstrated by Scarlett. Throughout the ballet, there are movements that look straight out of modern dance technique. This ballet has a full range of emotions, and basics of modern dance show emotion. If a person pulls her/his abdomen in and lets the contraction move the back into a curve, the onlooker will see pain or sorrow. Changes of direction are dramatic: What should I do? Is there someone to turn to? Scarlett has many ways to move large groups. In the ballet, there are people in a tavern. They are excited and questioning what is going on. That scene has thirteen dancers, including Victor. Scarlett differentiates these dancers: how do they stand, what do they do to look over a table, they break into separate directions or focus at the same spot. The ball to celebrate Victor’s and Elizabeth’s marriage features a large gathering of dancers. The couples dance filling most of the stage: Then, there are more dancers dancing closer and closer to each other in complex designs. In addition to the designs the dancers make, their designs, dancing so closely, and then more quickly; it becomes frightening.

The music composed by Lowell Liebermann fits every turn in the plot and the changes in the characters. Victor goes from tremendous joy at succeeding creating a new life from pieces of other bodies to feelings of guilt and terror. The music underscores the work of Scenic & Costume designer John McFarlane. There are gorgeous sets in the Frankenstein mansion, the frightening fight with the Creator in the garden, and the dreadful execution of innocent Justine.I was especially glad to see appropriate costumes for the story’s era. It is late 18thc., around the time of the American Revolution. Think of Ben Franklin and his experiments with a kite and electricity. The Lighting by David Finn told the story just as much as the dance and music. It will surprise you.

As the choreographer passed away, the ballet was staged by Lauren Strongin and Joseph Walsh; Walsh danced the role of Victor during this run.

The story is based on the book written by Mary Shelley, the wife of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, author of The Rights of Women, and William Godwin, philosopher and writer. One night, in 1818, near Geneva, she was with friends during a great storm. Fall out from a volcano eruption half way around the world made the world dark for days. They decided they should each write a scary story. Mary’s was Frankenstein. The science at the time sought more knowledge about electricity. There was philosophical debate and curiosity about what is life.

Cavan Conley as The Creature & Esteban Hernandez as Victor in Frankenstein ballet by Liam Scarlett performed by SF Ballet, photo LIndsey Rallo

Cavan Conley as The Creature & Esteban Hernandez as Victor in Frankenstein ballet by Liam Scarlett performed by SF Ballet, photo LIndsey Rallo

In the ballet’s Act I, scene 2, Victor’s mother dies. She was pregnant, fell to the floor, disappeared, but gave birth to Victor’s baby brother. That is a way of creating life. Victor wants to create life from body parts from the dead. He rejoices that the electricity he masters can create life, too. The Creature wants Victor to make another creature to be his partner. He learned to read – not explained much in the ballet – and learned that Victor wrote in his journal that his experiment had failed. The Creature became angry; he wanted love, but could he love?

The extraordinary, but real, Nathaniel Remez could not have been made. This other way of creating life is compared with Victor’s mother’s death and his brother’s birth. Remez performed majestically. He became the sad/angry Creature without love. His presence on stage was that of The Creature who killed the whole family, but Nathaniel Remez’s human beauty is not from AI.

Photos courtesy of San Francisco Ballet

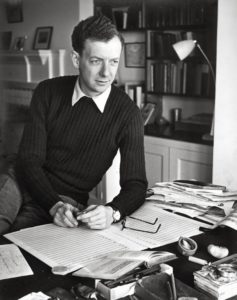

Benjamin Britten

Benjamin Britten Sasha Cooke, mezzo soprano

Sasha Cooke, mezzo soprano

Gabriela Ortiz, Composer

Gabriela Ortiz, Composer Gabriel

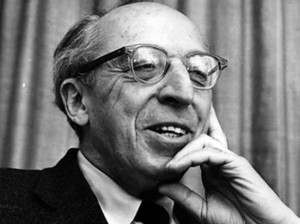

Gabriel Aaron Copland, composer (1900-1990)

Aaron Copland, composer (1900-1990) Joan Tower, composer

Joan Tower, composer Samuel Barber, composer

Samuel Barber, composer

Shostakovich at the piano

Shostakovich at the piano