May 24, 2025 – San Francisco Symphony at Davies Symphony Hall –

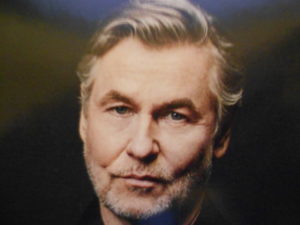

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Symphony, led the orchestra through a fascinating program: Chorale, by Magnus Lindberg; Violin Concerto, by Alban Berg; and The Firebird, by Igor Stravinsky. When Maestro Salonen entered the stage, the audience and the musicians stood to applaud him. It was very moving to see him, especially now, with only a few more concerts as the SF Symphony’ Music Director. The performance of The Firebird was an amazing celebration of his leadership.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Symphony, led the orchestra through a fascinating program: Chorale, by Magnus Lindberg; Violin Concerto, by Alban Berg; and The Firebird, by Igor Stravinsky. When Maestro Salonen entered the stage, the audience and the musicians stood to applaud him. It was very moving to see him, especially now, with only a few more concerts as the SF Symphony’ Music Director. The performance of The Firebird was an amazing celebration of his leadership.

Magnus Lindberg, composer (Born 1958 in Helsinki) Magnus Lindberg has been friends with Salonen since they were both students at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. His compositions can be complex; eventually, the works came to be assisted by a computer program he invented in order to create even higher complexities. Chorale was written in 2002 and premiered in 2002 conducted by Salonen with the Philharmonia Orchestra. It is 6 minutes long, with novel rhythms and inventive use of his instrumentation. Chorale was composed as a “companion piece” for Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto. The basis for the “companion” status is that both works use the Lutheran chorale, It is enough, which was set by Johann Sebastian Bach for his Cantata 60, O eternity, you word of thunder, long before.

Magnus Lindberg, composer (Born 1958 in Helsinki) Magnus Lindberg has been friends with Salonen since they were both students at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. His compositions can be complex; eventually, the works came to be assisted by a computer program he invented in order to create even higher complexities. Chorale was written in 2002 and premiered in 2002 conducted by Salonen with the Philharmonia Orchestra. It is 6 minutes long, with novel rhythms and inventive use of his instrumentation. Chorale was composed as a “companion piece” for Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto. The basis for the “companion” status is that both works use the Lutheran chorale, It is enough, which was set by Johann Sebastian Bach for his Cantata 60, O eternity, you word of thunder, long before.

Alban Berg, composer (1885 – 1935)

Alban Berg, composer (1885 – 1935)

Deep emotion is not something most music lovers would identify with Berg’s works, but this Violin Concerto, written in 1935, has deep sadness in every note. An eighteen year old daughter of friends died from polio. Berg delighted the girl; she was the daughter of Alma Mahler Werfel and the famous architect, Walter Gropius. It is true, her mother was Gustav Mahler’s widow. When the score was finished, Berg wrote “To the Memory of an Angel” on the manuscript. Berg had adopted the 12-tone principles developed by Arnold Schoenberg. As the composition grew, Berg discovered that the opening notes of Bach’s Cantata No. 60 matched the closing four notes of his concerto’s tone row. Here are the words of the Cantata which also inspired Magnus Lindberg Chorale:

It is enough!/Lord, if it pleases you./Unshackle me at last. /My Jesus comes;/I bid the world goodnight./I travel to the heavenly home./I surely travel there in peace,/My troubles left below. It is enough! It is enough!

The Violin Concerto translates Manon Gropius’ pain and struggles into music. The second movement is frightening; one cannot avoid imagining the lovely girl knowing that she was dying. There are two harmonies that put forth the complete 12-tone row from the lowest to the highest. It reaches to three octaves higher. The violin does that, but the other instruments go so low as possible. A tragic event, Berg died of blood poisoning Christmas eve day. This was his only solo concerto. Isabelle Faust, solo violin, played with direct feeling and strength.

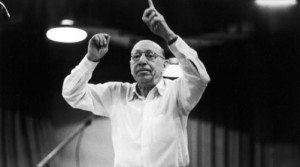

Igor Stravinsky, composer (1882 -1971)

Igor Stravinsky, composer (1882 -1971)

Stravinsky’s The Firebird was a fabulous showpiece. Parisians who heard the premiere all reported that it knocked their socks off.

It was composed 1909-1910 and created the fame and style of Stravinsky. Serge Diaghilev, The Magnificent Impresario, with Michel Fokine, dancer-choreographer, the Ballet Russe, made Paris its home. They reached into Russian folk tales and came up with the Firebird and Kashchei the Deathless, a personification of evil. Three well known composers turned down the opportunity to make music for that. Stravinsky, who had only orchestrated Chopin piano pieces for Diaghilev, went for it. At age 27, his career going nowhere, Stravinsky stayed in St. Petersburg and composed. The meetings of Fokine and Stravinsky, improvising movement and music, must have been electric. Much of the music came from Russian folk tunes and, as written by Benjamin Pesetsky for the program notes, “even his harmonic sleights-of-hand and modern orchestrational wizardies don’t stray far from those of Rimsky-Korsakov.” The Firebird was good and the Kashchei was terrible; Stravinsky made happy music that one might be able to hum (for the Firebird) and dark harmonies that were bad (for Kashchei). Why not? The story ballet energized the music; the costumes brought color to the audience’s imagination. Act One brings the Dance of the Firebird. The violins, clarinets, and flutes play for the magical bird. Prince Ivan discovers thirteen princesses. The thirteen ballerinas dance a version of a khorovod, a Russian folkdance in a circle. Kashchei and his cronies kidnap the Prince. Kashchei must dance the Infernal Dance accompanied by timpani, brass, and xylophone. Good will win: the Firebird’s Lullaby, accompanied especially by the bassoon, shows peace can return. There is a wonderful horn solo before the entire orchestra brings powerful goodness. The audience was left to applaud and even shout out. Not quite a year after The Firebird, Stravinsky, having learned that ballet is the way, composed Petrushka using the vast array of percussion, rhythms, harps, everything. Last night’s performance had a glorious ending.

Yuja

Yuja