PhotoFairs returned to San Francisco, February 22 – 24. The vast exhibition at San Francisco’s Fort Mason included works from 40 galleries from 15 countries and 26 cities. With offices in Shanghai, London, and San Francisco, PhotoFairs shows photography and moving image work it considers “cutting edge.” For this viewer, wandering through the almost endless display of photographs, the work that most attracted my attention included images which suggested stories. These were not specific narratives, but the onlooker could imagine, was even invited to imagine, what had happened.

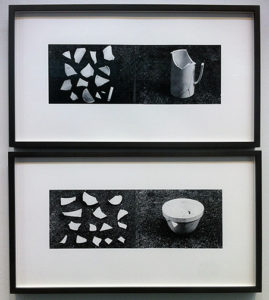

Amikam Toren’s works, Replacing No. 1, 1975(bottom photo) and Replacing No. 2, 1975 (top) engaged my eye and thoughts. In each photograph, on the left there are broken pieces and on the right there is an object that has been made by putting the pieces together. One sees the cracks in the “finished” product and also some flaws which might mean that a piece is missing. Why was it broken? Why was it mended? Is the broken thing still the same thing it was before it was broken?

Amikam Toren’s works, Replacing No. 1, 1975(bottom photo) and Replacing No. 2, 1975 (top) engaged my eye and thoughts. In each photograph, on the left there are broken pieces and on the right there is an object that has been made by putting the pieces together. One sees the cracks in the “finished” product and also some flaws which might mean that a piece is missing. Why was it broken? Why was it mended? Is the broken thing still the same thing it was before it was broken?

Replacing No. 1, 1975, Amikam Toren

Replacing No. 1, 1975, Amikam Toren

Replacing No. 2, 1975, Amikam Toren

Replacing No. 2, 1975, Amikam Toren

In these closer views does the title “Replacing,” mean that all the pieces have been put back in place or that the broken thing now replaces what was once whole? Can Humpty Dumpty be put together again and still be what he was?

Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, Apartment Windows, 1977, invites as many stories as there are windows; actually, there are more possibilities than windows.

Apartment Windows, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1977.

Apartment Windows, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1977.

Some windows are open, others completely closed. Some have just the drapes pulled together, some have shades and drapes. What is happening on the other side of the windows? The various approaches to open, closed, covered, partly covered invites speculation about the stories within each apartment. Who closed the drapes or pulled the shades all the way or part of the way down? Why was the choice made to cover the window rather than leave it open? When the window is open, it’s not just that someone outside could look in, but also that someone inside could look out.

Tang Feng Gallery of Miaoli City, Taiwan, presented photographs by two artists, one working in classic black and white and the other in color in a smaller format. The images are evocative, seemingly straightforward, suggestive of mystery. A man sits in a decorated cart; a pedicab driver, he is taking time to relax. The photographer captures the moment from above, showing the man momentarily at rest.

The Native Gaze 0005, by Chang-Ling, 2016

The Native Gaze 0005, by Chang-Ling, 2016 The Native Gaze 0006, by Chang-Ling, 2016

The Native Gaze 0006, by Chang-Ling, 2016

In Chang-Ling’s The Native Gaze 0006, something photographic is happening. A young woman turns to talk with someone we don’t see. Everyone else is focused on something happening beneath the arc of balloons. Its intense color, the light coming from at least three different sources, and the young woman looking a different way play with the onlooker’s ability to know what is happening.

The Old Man and the House He Built, 2014, Wei-ming Yuan

The Old Man and the House He Built, 2014, Wei-ming Yuan

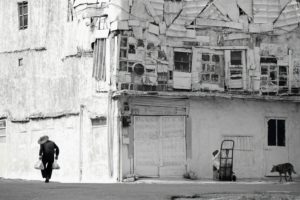

In The Old Man and the House He Built, the Old Man walks past a house that appears to be built of mismatched materials. How did he build something that could stay standing with these objects? There is a story behind that house, that man, and the equally old dog which might be following him. The onlooker cannot know the whole story or all the stories, but it is fascinating to wonder about it.

Tai Chi, by Wei-ming Yuan, 2005

Tai Chi, by Wei-ming Yuan, 2005

The artist also shows images which become nearly abstract due to his closeness to the subject or the movement in the subject. In Tai Chi, he looks up through the rock of a slot canyon in the American West.

These selections are not the most “experimental” of the works shown, but they held my interest for the stories they might tell.

Photographs of the photographs by Jonathan Clark, Mountain View, CA

See www.livelyfoundation.org/wordpress/?s=photofairs Hedgehog Highlights article about PhotoFairs, January 29, 2017

Notes on photos: Amikam Toren (Israeli, b. 1945), Replacing No. 1, 1975; Replacing No. 2, 1975; Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1948-1989), Apartment Windows, 1977; Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation Estate; Weinstein Hammons Gallery, Minneapolis; Chang-Ling (Taiwan, 1975) and Wei-ming Yuan (China, 1948), Tang Feng Gallery, Miaoli City, Taiwan.

Andrey Boyreko (Left), Leonard Bernstein (Right)

Andrey Boyreko (Left), Leonard Bernstein (Right) Vadim Gluzman

Vadim Gluzman Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich

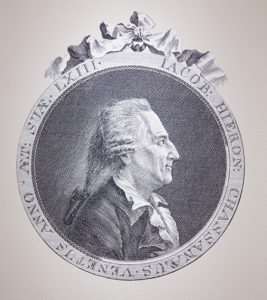

Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798)

Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798)

(Left) Franceso Guardi (Italian, 1712-1793) The Ridotto of Palazzo Dandolo at San Moise with Masked Figures Conversing ca. 1750. The ridotti were state sponsored gambling rooms, sometimes places of music and dancing. Everyone was required to wear masks which made it easier for thieves and prostitutes to mix with the elite. (Right) 18th c. Sedan chair which belonged to Alma Spreckles, founder of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor

(Left) Franceso Guardi (Italian, 1712-1793) The Ridotto of Palazzo Dandolo at San Moise with Masked Figures Conversing ca. 1750. The ridotti were state sponsored gambling rooms, sometimes places of music and dancing. Everyone was required to wear masks which made it easier for thieves and prostitutes to mix with the elite. (Right) 18th c. Sedan chair which belonged to Alma Spreckles, founder of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor

(Left)

(Left)

from left: Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Garrick Ohlsson

from left: Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Garrick Ohlsson

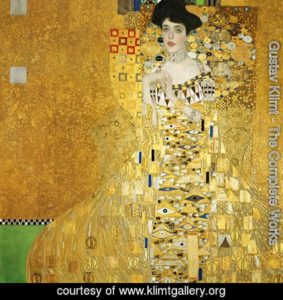

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) (not part of this exhibition)

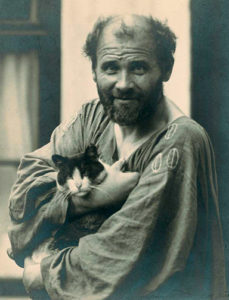

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) (not part of this exhibition) Gustav Klimt and his Cat (Katze), photo by Moritz Nahr

Gustav Klimt and his Cat (Katze), photo by Moritz Nahr

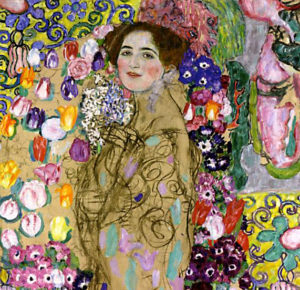

Klimt, The Virgin, 1913

Klimt, The Virgin, 1913 Emanuel Ax

Emanuel Ax

Wolfgang Amadeo Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeo Mozart Arnold Schoenberg, photograph by Man Ray

Arnold Schoenberg, photograph by Man Ray Medieval woodcut of trickster, Tilll Eulenspiegel, courtesy, San Franciso Symphony

Medieval woodcut of trickster, Tilll Eulenspiegel, courtesy, San Franciso Symphony Reconstruction of Trojan Archer, 2005. Original: Greece, Aegina, ca.480 B.C.E.Glyptothek Munich. Copy synthetic marblecast with natural pigments in eg tempera, lead, and wood, height 37 3/4in. Leibieghaus Sculpture Collection (Polychromy Research Project), Frankfurt, on loan from the Universit of Heidelberg, LG157. picture courtesy Fine Arts Museums San Francisco.

Reconstruction of Trojan Archer, 2005. Original: Greece, Aegina, ca.480 B.C.E.Glyptothek Munich. Copy synthetic marblecast with natural pigments in eg tempera, lead, and wood, height 37 3/4in. Leibieghaus Sculpture Collection (Polychromy Research Project), Frankfurt, on loan from the Universit of Heidelberg, LG157. picture courtesy Fine Arts Museums San Francisco.

Shambhavi Dandekar, Kathak artist and director of SISK, the Shambhavi Institute of Kathak, of California and India

Shambhavi Dandekar, Kathak artist and director of SISK, the Shambhavi Institute of Kathak, of California and India Tejaswini Sathe, Guest Artist, Director of SISK, India

Tejaswini Sathe, Guest Artist, Director of SISK, India Ghungroos/Footbells worn by Kathak dancers

Ghungroos/Footbells worn by Kathak dancers Tabla Drums

Tabla Drums Tejaswini Sathe and Shambhavi Dandekar

Tejaswini Sathe and Shambhavi Dandekar