It was a stroke of luck to be in the San Francisco Symphony’s audience on Dec. 3 to experience Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. The music acknowledges struggles, yearning, even hints at despair and still it expands into a universe, a glorious affirmation of life. I read another writer call this music an “old warhorse;” I could never think that. There are good reasons why everyone cherishes it – mostly everyone. Sometimes a person gets a Vitamin B shot. Sometimes it takes a Jacuzzi. This symphony is what works every time. It opens the world, lets the listener feel part of it, realize how all life can befriend other lives, and feel the joy propelling us through this phenomenal experience.

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Dec. 16,1770 – March 26, 1827

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Dec. 16,1770 – March 26, 1827

The concert’s opening selections were both enjoying premier performances at the SF Symphony. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Ballade, Opus 33, written in 1898, was the composer’s first big, prestigious presentation. The Three Choirs Festival invited Edward Elgar to present a short piece for orchestra, but he was too busy. He recommended the young Coleridge-Taylor as “he is far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the young men.” The Ballade is lyrical and uses interesting back and forth themes and rhythms trading from one section to another. It is a delightful rondo. The listener thinks she has caught the pattern just before there is a shift in the part of the orchestra expressing the energetic song. It is a delightful piece of music. Sadly, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor died, age 32. from a combination of over work and illness. His star had shone brightly for too short a time.

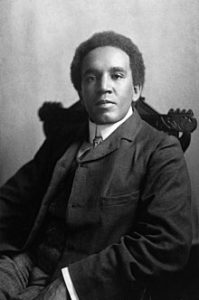

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor August 15, 1875- September 1, 1912

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor August 15, 1875- September 1, 1912

Emerge, by Michael Abels, is a fascinating narrative in music of what happened to musicians and what they did about it during the pandemic. It was a bonus to hear the recorded voice of the composer describing the progress from individuals playing music on their own – do you remember videos of musicians playing great music alone in their kitchens and sometimes a whole ensemble all playing in separate places but somehow making the music together? Then, in Emerge, they gather to play together. Blues phrases happen but in a canon instead of musicians playing together. There are scales from the strings and wind instruments and, the composer has written, “When the brass get involved, the strings are finally able to play a melody all together in unison… The scale volley becomes faster until it finally comes together…” The music absolutely does what the composer intends. It is full of a happy kind of energy. Music can be made again, full out. There is a feeling of rejoicing and dancing forward. Mr. Abels has won many awards for his music. The SFS audience wanted to give him another one that night

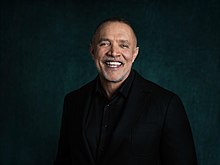

Michael Abels

Michael Abels

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Opus 125 (1824) is huge from any perspective. It lasts about 65 minutes. It employs the entire orchestra plus four solo vocalists – Gabriella Reyes, soprano, Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano, Issachah Savage, tenor, Reginald Smith, Jr., baritone/bass, and a grand chorus of singers. The SFS Chorus includes 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer singers. Together these artists embody a population, a world. The conductor, Xian Zhang, was a revelation. Her deep knowledge of the music and her dedication to bring out for all of us what Beethoven put in were visible. She encompassed all the music and the musicians in her own being through her energetic, compelling leadership of the orchestra. She is exciting to watch; more than that, she made each sound matter, and, by the way, matter is energy, too.

This symphony is a journey for each of us and all of us together. I really do not like the constant use of “it’s a journey” for everything, but being moved by this music takes us on a journey from dense darkness to brilliant light. Even knowing the light will break through because one has heard this music before, it comes as a surprise. At the very beginning, one cannot say what is happening or what is surrounding us. Then, the enormous sound of the D minor takes our breath away. Immediately we hear different themes pelting us with more blows pounded by the timpani. Once in a quick while, we hear what might be tiny paws running past us while a Beethoven parkland message is played. The Adagio movement flows gracefully around us. It seems to promise a peaceful presence which has not yet arrived. We may hope for it, but there is no promise that it will come. This quiet sound, almost like breathing, is interrupted by the orchestra. Is it a new setting, a new way of being? Or has all we have traveled through: fear, failure, feelings beyond mere sadness changed us? The music presents more variations until the bass singer announces, a capella, Beethoven’s own message; “Oh, Friends, no more of these sounds!/Instead, let’s strike up a song that’s more pleasant,/And more joyful.” We are rewarded with the most uplifting of moments hearing the great sound of the Chorus and Orchestra together. Schiller’s poem praises Nature which gives us “kisses and grapevines,/a friend, faithful unto death./Pleasure was given even to the lowly worm,/And the cherub stands before God.” Human lives and the lives of worms all feel joy. There is frequent carping against this poem, and yet, in it Beethoven found what he was looking for: a statement including all life. No wonder the audience literally jumped and cheered.

photo credits: Michael Abels, by Eric Schwabel; Xian Zhang, by B. Ealovega

Conductor Xian Zhang

Conductor Xian Zhang