Vacation time returns! Vaccinated and raring to go? Pick up beautiful books from The Lively Foundation to read and enjoy while out in the sun at home or farther afield. Lively books now on offer include The Dancer’s Garden and The Story of Our Butterflies, by Leslie Friedman with photos by Jonathan Clark & Leslie Friedman and OTTAWA: 1967, a collection of photographs by Jonathan Clark of the small town in Northern Illinois where he grew up.

OTTAWA: 1967 is an outstanding collection of photographs taken by Jonathan Clark, internationally renown, award winning photographer. Together these images capture the essence of lives in a time that is gone. The place is still there, but so much has changed. Published by Nazraeli Press, these images will light up your imagination and memory giving you an entry to what could be a foreign country though it is not so far away.

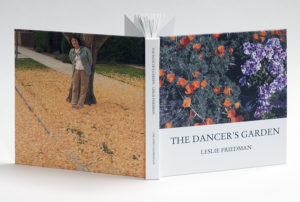

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, by Leslie Friedman with photographs by Jonathan Clark and Leslie Friedman. Comments on this book are full of praise: “I love it. It is a perfect book, in conception and execution. You are a marvelous writer, as I expected, and I am particularly fond of short essays. The scale and layout are just right…”Diana Ketcham, HOUSE & GARDEN, EDITOR (ret.), Books Editor, THE OAKLAND TRIBUNE (ret.) “There is so much delight and poetry and wisdom to be found in the garden and in your book!” S. Abe, CA Academy of Sciences (ret.)

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, by Leslie Friedman with photographs by Jonathan Clark and Leslie Friedman. Comments on this book are full of praise: “I love it. It is a perfect book, in conception and execution. You are a marvelous writer, as I expected, and I am particularly fond of short essays. The scale and layout are just right…”Diana Ketcham, HOUSE & GARDEN, EDITOR (ret.), Books Editor, THE OAKLAND TRIBUNE (ret.) “There is so much delight and poetry and wisdom to be found in the garden and in your book!” S. Abe, CA Academy of Sciences (ret.)

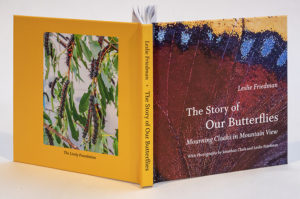

THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: Mourning Cloaks in Mountain View, “This is a wonderful book and I look forward to sharing it with the rest of the staff here.” Joe Melisi, Center for Biological Diversity, national conservation organization, Tucson, AZ; “Leslie Friedman is an historian, a dancer and choreographer, and now a perceptive writer about nature….in a second splendid work she takes wing into the world of butterflies….One is grateful for this delightful book, so well written and illustrated.” Peter Stansky, Author, Historian, Professor Stanford University.

THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: Mourning Cloaks in Mountain View, “This is a wonderful book and I look forward to sharing it with the rest of the staff here.” Joe Melisi, Center for Biological Diversity, national conservation organization, Tucson, AZ; “Leslie Friedman is an historian, a dancer and choreographer, and now a perceptive writer about nature….in a second splendid work she takes wing into the world of butterflies….One is grateful for this delightful book, so well written and illustrated.” Peter Stansky, Author, Historian, Professor Stanford University.

I WANT THEM! HOW DO I GET THEM?

OTTAWA: 1967 is available from The Lively Foundation. These books are from the artist’s own collection. Cost: $50 plus $6 for mailing. Please mail your check made out to The Lively Foundation to The Lively Foundation, 550 Mountain View Avenue, Mountain View, CA 94041-1941. If you need to use a credit card, please see instructions for PayPal below.

THE DANCER’S GARDEN is available from Bird & Beckett Books & Records, San Francisco, and from The Lively Foundation. Stanford Bookstore currently sold out of it. You can contact the Stanford Bookstore and request it. Cost is $42; $45 which includes mailing.

THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: MOURNING CLOAKS IN MOUNTAIN VIEW is available from Bird & Beckett Books & Records, The Lively Foundation, and Stanford Bookstore. Cost is $29.95 plus $5 for mailing.

Bird & Beckett Books & Records, 415/586-3733; 653 Chenery St., SF 94131; eric@birdbeckett.com; Hours: Tues-Sun Noon-6 p.m.

Stanford Bookstore, 650/329-1217; Lasuen Mall/White Plaza, Stanford Univ. CA 94305; stanford@bkstr.com; Hours: Mon-Thurs 11 a.m.-7 p.m.; Fri & Sat 10 a.m.- 7 p.m; Sun 11 a.m.- 6 a.m.

The Lively Foundation, livelyfoundation@sbcglobal.net, 650/969-4110, 550 Mountain View Ave, Mountain View, CA 94041- to buy with a ccard from Lively, please go to the landing page of this blog, scroll down to see the PayPal logo, click on that to pay with ccard. Please add $1.15 to credit card purchases. Thank you!

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, Peter Stansky! Frances and Charles Field Professor Emeritus of modern British History, he joined the Stanford University History Department in1968. He served as Chair of the History Department for 7 years. He is the author of many, many books* and internationally honored as the shining light of his field, On Jan. 15, 2022, Stanford honored him with a Symposium on topics of his special interests: William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement in England; Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group; George Orwell. On Jan. 17 a gathering of students, many now distinguished professors and authors themselves, and friends from across the US and the world thanked him for his friendship, encouragement, enlightenment, and lively verve. Beginning today, Hedgehog Highlights on the livelyblog will feature reviews of his recent books. Thanks to The Institute for Historical Studies and its editor, Maria Sakovich, for permission to re-publish the reviews that appeared in TIHS publication which were written by Leslie Friedman, one of Professor Stansky’s Stanford Ph.D.s.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, Peter Stansky! Frances and Charles Field Professor Emeritus of modern British History, he joined the Stanford University History Department in1968. He served as Chair of the History Department for 7 years. He is the author of many, many books* and internationally honored as the shining light of his field, On Jan. 15, 2022, Stanford honored him with a Symposium on topics of his special interests: William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement in England; Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group; George Orwell. On Jan. 17 a gathering of students, many now distinguished professors and authors themselves, and friends from across the US and the world thanked him for his friendship, encouragement, enlightenment, and lively verve. Beginning today, Hedgehog Highlights on the livelyblog will feature reviews of his recent books. Thanks to The Institute for Historical Studies and its editor, Maria Sakovich, for permission to re-publish the reviews that appeared in TIHS publication which were written by Leslie Friedman, one of Professor Stansky’s Stanford Ph.D.s.

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, by Leslie Friedman with photographs by Jonathan Clark and Leslie

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, by Leslie Friedman with photographs by Jonathan Clark and Leslie  J

J Jonathan Clark, better known as a photographer and fine art printer, will read the role of Danny. Leslie Friedman, better known as a dancer/choreographer, will read the role of Lily.

Jonathan Clark, better known as a photographer and fine art printer, will read the role of Danny. Leslie Friedman, better known as a dancer/choreographer, will read the role of Lily. Leslie Friedman – best known as a dancer- is the playwright of The Exhibitionist.

Leslie Friedman – best known as a dancer- is the playwright of The Exhibitionist.  Shambhavi Dandekar

Shambhavi Dandekar

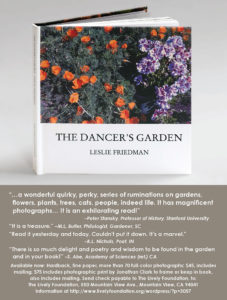

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, This beautiful book has text and photos by Leslie Friedman with additional photos by artist Jonathan Clark and one by Dennis Parks, English actor. Review and comments on this book call it “a treasure,” “a marvel,” and “a wonderful quirky, perky series of ruminations on gardens, flowers, plants, trees, cats, people, indeed life. It has magnificent photographs…It is an exhilarating read!”

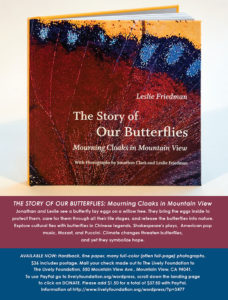

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, This beautiful book has text and photos by Leslie Friedman with additional photos by artist Jonathan Clark and one by Dennis Parks, English actor. Review and comments on this book call it “a treasure,” “a marvel,” and “a wonderful quirky, perky series of ruminations on gardens, flowers, plants, trees, cats, people, indeed life. It has magnificent photographs…It is an exhilarating read!” THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: Mourning Cloaks in Mountain View, Text by Leslie Friedman with photos by Jonathan Clark and Leslie Friedman. Jonathan and Leslie see a butterfly lay eggs on a willow tree. They bring the eggs inside to protect them, care for them through all their life stages, and release the butterflies into nature. Explore cultural ties with butterflies in Chinese legends, Shakespeare’s plays, American pop music, Mozart and Puccini. Climate change threatens butterflies and yet they symbolize hope.

THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: Mourning Cloaks in Mountain View, Text by Leslie Friedman with photos by Jonathan Clark and Leslie Friedman. Jonathan and Leslie see a butterfly lay eggs on a willow tree. They bring the eggs inside to protect them, care for them through all their life stages, and release the butterflies into nature. Explore cultural ties with butterflies in Chinese legends, Shakespeare’s plays, American pop music, Mozart and Puccini. Climate change threatens butterflies and yet they symbolize hope.