June 21, 2024: Do not be upset. I know that Bruckner is not labelled a Romantic composer, but he gave his Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, Romantic. the name “the Romantic” after he completed it. Schumann, was a Romantic in his music and his life. His Piano Concerto in A minor, Opus 54 was his only piano concerto, but it is a perfect one. Why are these two composers on the same program? Each one created a change in the art. Schumann’s significant change is a new way to make a concerto. Bruckner made lasting changes in the development of symphonic movements. There are stories behind each innovation.

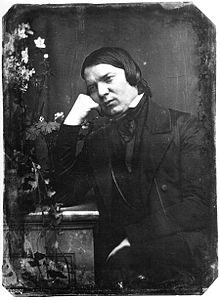

Robert Schumann, composer (1810 -1856)

Robert Schumann, composer (1810 -1856)

THE COMPOSER

He looks so troubled in this picture. For a long time I have felt that Schumann did not get enough attention in our modern and/or post-modern era. Very unfair. As you see in his dates, he lived only 46 years. Mozart and Mendelssohn both died before they reached 40. Sadly, that is one of the facts people will note. Surely, Mozart and Mendelssohn deserve every possible praise, but the brevity of their lives, and of Schumann’s, should be on some kind of celestial list. And Schumann spent the last part of his life in an asylum. He fell in love with Clara Wieck, widely recognized as the great concert pianist of Europe. To complete the romantic story, her father would not allow them to marry. However, they married anyway. She continued to perform, to teach, and to compose. Her work supported the family. She had eight children. She performed her husband’s music and would listen to the new works. Schumann was very intelligent in other arenas, too. He founded a journal, the Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik, in 1834, and wrote for it and edited it for ten years. He had studied law at Leipzig and Heidelberg, but he was a musician. Music and Clara were his life.

His Piano Concerto in A minor, Opus 54 was something new. He began a work he called Phantasie, in 1827. In 1839, he published an essay about piano concertos in the Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik. He did not like the existing concerto form of the orchestra and soloist being separated mainly to show off the virtuoso piano performance. He imagined more interaction of the orchestra and soloist making the music together.

Clara Schumann, pianist, composer, wife of Robert Schumann (1819 – 1896).

Clara Schumann, pianist, composer, wife of Robert Schumann (1819 – 1896).

THE CONCERTO

Schumann wrote that “the orchestra, no longer a mere spectator, may interweave its manifold facets into the scene.” He wrote four more attempts at the new concerto, but they were only attempts. Clara played the piece and declared the Phantasie good. “The piano is most skillfully interwoven with the orchestra; it is impossible to think of one without the other.” Schumann was not there yet. It did not get published; Schumann felt something was missing. Schumann revised the Phantasie in 1845, making it a three movement concerto. It may not be the most challenging concerto, but he brought together orchestra and soloist together to make music. It is an act of beauty. The “interwoven” sources of the music also weave a spell for the listener.

Yefim Bronfman, Pianist

Yefim Bronfman, Pianist

The San Francisco Symphony, led by Music Director, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and the soloist, Yefim Bronfman, made the music play above merely wonderful. Schumann would be happy to know how seamlessly the music came through the team work of all. When the piano introduces itself at the beginning, the oboe and bassoon present the theme. Schumann made the work without the usual orchestra and soloist’s separate excitement. The idea of connecting the roles of soloist and orchestra is present throughout. Schumann himself wrote the piano’s cadenza, and it is glorious. None of the orchestra’s instruments is lost. The first violins swell as the piano presents a second theme. A solo clarinet is heard clearly over the quiet playing of the strings. This concerto shows what is created when every instrument’s character plays itself and is part of the company as well as having its own, individual, musical life. There is little one might write about Yefim Bronfman. His performance was beyond extravagant superlatives. He plays the soul of the music. There are places in the Concerto when the piano is delicate, almost quiet, small. Those moments were some of the biggest experiences of the Concerto. The audience could not let him go. There were, maybe, six encores. After the first two or three, Bronfman played a Rachmaninoff piece, Prelude in G minor (op. 23 no. 5), it had unique rhythms and a changing pattern. Fascinating and strange. The audience carried on applauding and shouting bravos until a few at a time gradually trickled to the exits.

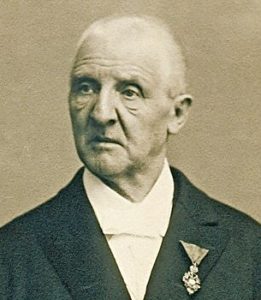

Anton Bruckner, composer, organist 1824-1996

Anton Bruckner, composer, organist 1824-1996

THE SYMPHONY

The SF Symphony led by Music Director, Esa-Pekka Salonen, gave a powerful and insightful performance of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, Romantic. The orchestra represented Bruckner’s unique approach to every note. This is a great symphony in every sense of the word; the music is marvelous and the symphony is a long one. Bruckner gives the listener new sounds and new roles for particular instruments. There are dissonant notes and momentary rests. They are surprising. Then, the listener realizes that these novel aspects are part of Bruckner’s mystery. Here is a master of orchestration and counterpoint who knows the use of an out of the way path wins the music lover’s attention. The Symphony No. 4 has musical references to hunting in its Scherzo and other movements. The horns are the stars of this Symphony. One can picture the “nobility” riding through a forest. This is part of the Romanticism that was sweeping across Europe. Movements develop slowly; there will be a change to lively dance music; then a wistful encounter of characters. Bruckner must have surprised himself so much as his audiences were surprised when, long after the Symphony’s debut, he wrote a note of what images could float before one’s eyes:

“Medieval city- dawn-morning calls sound from the towers-the gates open-on proud steeds the knights ride into the open-woodland magic embraces them-forest murmurs-bird songs-and thuse the Romantic picture unfolds.”*

There are more wind instruments playing music that does suggest the natural world awakening, and, through the grandeur of the Symphony, there are suggestions of folk music. Bruckner’s view is broad as though he looks across all directions for the vast earth, brooks, and trees and stretches his musical vision to encompass the living world and even beyond. He takes our breaths away in a dazzling finale that draws together darkness and distant light.

THE COMPOSER

Bruckner’s life could have followed his father’s and grandfather’s paths as a schoolmaster and organist in the Austrian village of Ansfelden When his father died, his mother took him to St. Florian’s, a monastery-school. Bruckner’s attachment to St. Florian’s lasted throughout his life. He began teaching music at St. Florian’s soon after his education there ended. Before St. Florian’s he had music education through his father and, when his father was ill, Anton played the organ in the church. He spent ten years on St. Florian’s music faculty. He left to live in Linz, 1856, and began to write seriously. There was a popular song for male-voice chorus, “Germanenzug,” 1863; Psalm LX11, for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, 1863; Symphony in F minor, his first symphony, 1863; a great Mass in D major, his first mass, 1864. Beginning in 1855, he studied counterpoint and harmony with Simon Sechter. Bruckner felt he was not sufficiently prepared for composing. Sechter was considered the best teacher, and Bruckner spent six years studying with him although Sechter was in Vienna and Bruckner in Linz. Then, he took up the study of orchestration and musical form from Otto Kitzler, also considered the best teacher in these areas. Assigning himself to these studies reveals Bruckner’s hunger for learning and perfectionist tendencies.

Life in Linz was obviously more stimulating for Bruckner than his previous home. In Linz, he wrote two more symphonies; one in D minor -called Zero Symphony – and Symphony #1 in C minor. He wrote two great Masses: one in E minor, 1866; and one in F minor, 1867-1868. The E minor mass kept to strict polyphonic style for an 8 part chorus and brass instruments. The F minor established a new kind of “symphonic mass,” for orchestra and chorus.

If Linz was a helpful atmosphere for him, when Bruckner moved to Vienna, 1868, he began a period of creative production. He had been studying his music theory lessons and still taught music and played the organ. It was a hard working life. When he arrived in Vienna, he was able to succeed Sechter’s position as professor of harmony and counterpoint at the Vienna Conservatory and had private students. The University of Vienna gave him a position in their faculty, too. Before Vienna, he had had a nervous breakdown. Overwork or something physical? There is no answer, except that Vienna gave him so much more. All his training and work opened the door to important positions. Starting in 1868, he was the court chapel organist, and from 1875 onward he was Vice Librarian and Second Singing Master for the choristers. These positions lack lofty names, but they added to his financial security and visibility.

Bruckner saw Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman and Tannhauser, in Linz, and traveled to Munich to see Tristan and Isolde. He met Wagner in 1865 and became a Wagnerian. This placed him in the midst of battles between followers of Wagner and those who preferred Brahms. Some leading critics, especially Eduard Hanslick, made it difficult for Bruckner’s work to get the approval and attention needed to move his work forward.HNe toured as an organist. He performed in Paris and Nancy, 1869, and London, 1871, performing at the Crystal Palace exhibiton five times. His virtuoso organ playing and his improvisation on the organ fascinated audiences. It is said that his improvisations were spectacular. Later he made journeys within Germany: Leipzig, Munich, and Berlin were frequent venues. There were also conductors who were enthusiastic about his music. These were Nikisch, Levi, Mottl, Mahler, and Ochs. His symphonies and masses were greeted with admiration or dislike, again because of the politics of Wagner vs. Brahms. Mahler especially supported Bruckner’s work. He made the first pianoforte arrangement of Symphony No. 3 and conducted the first performance of Symphony No. 6, in 1899.

Anton Bruckner’s made changes that contributed to the development of symphonies. As he was a dedicated student of orchestration, harmony, counterpoint, the changes will mean the most to musicians and students, but the changes affect what an audience hears. (A) he introduced a third subject in the exposition. (B) A tendency to telescope development and recapitulation which make the movement split into 2 main parts. This is most noticeable in the first and fourth movements of his Symphony No. 9. (C) shifting the power center to a finale which can end with repetition of the main themes of early movements (D) linking movements by shared themes as in Adagio and Scherzo in Symphony No. 5 and Scherzo and Finale of Symphony No. 4.

These innovations stepped away from the classical forms of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Bruckner broadened the possibilities of great symphonies.

*Quotation taken from SFS program note by james M. Keller.

Marc-André Hamelin (photo by Fran Kaufman)

Marc-André Hamelin (photo by Fran Kaufman) Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)