November 21, 2015 – Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco – San Francisco Symphony members performed beautifully in an extraordinary, musical adventure. Alexi Kenney played violin and served as leader for the group. This was a Baroque presentation: all the musicians stood while playing; that is all except the harpsichordist. The music was equally very old, ca. 1664 and early 18th century; and very new. The Baroque sound is different than Classical and Romantic. We have lost touch from the 18thc. Early 18thc. humans walking around with music in their heads had delightful music to hear. Mr. Kenney played brilliantly. His great energy and devotion to the music spread to the other musicians as well as the audience.

Olli Mustonen, composer ( born 1967)

The opening piece was the only one composed in 2000. Nonetto II for Strings, by Finnish composer Olli Mustonen, has traces of Baroque music while it is still modern. It is a wonderful, appealing piece which can draw the listener’s warm attention. It was fifteen minutes long, and I would have happily let it go on. I referred to the program to be sure it has no Baroque ancestry. It is all modern with the Baroque musicians sending an occasional telegram for their part in Mustonen’s innovations.

Barbara Strozzi, composer, singer (1619 – 1677)

A very brief piece, “Che si puo fare,” Opus 8, no. 6., by Barbara Strozzi, about 5 minutes, was arranged by Alexi Kenney. Barbara Strozzi was a popular composer and singer. Anything about her that is known for sure is unusual in mid-17thc. An Italian woman in Venice, publishing her own compositions, and published eight volumes of vocal music. These songs were secular, not for the church. According to the program note, “she may have been the most published composer within her genre in Venice.” She died young, 58; it took 300 years before she was rediscovered. Its brevity made it difficult to get into it, but it has the same Baroque, tangy sound that seems so new to jaded twenty-first century listeners. A paraphrase of Ms Strozzi song:

“What can I do? The stars have no pity. If the gods won’t grant me peace, what can I do?/ What can I say? The heavens keep sending me disaster…What can I say?” If Ms Strozzi had read Sappho, they could sing a duet.

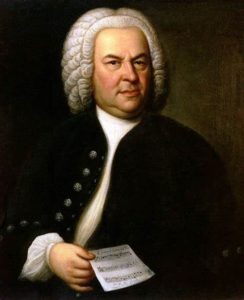

Johann Sebastian Bach, composer (1685 -1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach, composer (1685 -1750)

Bach wanted to move in order to get a better job. He wrote the Brandenburg concertos to tempt Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt to bring Bach to his employment. It did not work. Instead, Bach moved to Leipzig in 1723. Bach’s concertos disappeared until 1849. The Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 was a new kind of concerto. This one has violin, flute, and harpsichord soloists. It was a careful mix of the old style of concerto grosso and the new concerto with more solos. This was a great, tuneful, rhythmic Bach. The musicians were all excellent. I wished the harpsichord could be heard better while playing with the strings. Not the harpsichordist fault; when he played solo one could hear very well. Possibly, the instrument would be better heard in a smaller venue. When I was a kid, friends wanted to play pop music in their piano classes, I wanted more Bach. Still do.

Antonio Vivaldi, composer, violinist (1678 – 1741)

The Four Seasons, Opus 8, nos. 1-4, by Antonio Vivaldi, has become favorite “classical” music. Vivaldi worked at the Ospedale della Pieta in addition to being the “master of music in Italy.” The Ospedale della Pieta was a home and music school for female orphans and illegitimate daughters of wealthy nobles. It interests me that some of the music was written by Vivaldi years before he wrote The Four Seasons. Then, he composed new additions some of which were more complex. One of his major, new approaches was to write poetry and music all together in pictures of the seasons. Spring paints a picture of buds opening, singing birds returning, sudden storms come and then bring quiet. In the middle of the 20thc., The Four Seasons began to be popular again. Perhaps now, its loveliness can come back in our not so lovely era.

Itzhak Perlman

Itzhak Perlman