Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, February 19 — The first half of the concert was Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D major, Opus 36, composed 1801-02. The SF Symphony played at The Top. After intermission: Symphony No. 7 in A major, Opus 92, 1811-12. Again, the SF Symphony played magnificently. Jaap Van Zweden conducted brilliantly. The two symphonies are different in so many ways, and I wanted the SFS to play them both again. I am still excited by the music. I talked with another music lover. She told me that she knows Beethoven’s music, but had not known about #2 and #7. She brushed them off. If she did not know them, they must be just extras, not being the #5 or #9. However, these symphonies are INCREDIBLE. My suggestion is if you were not able to be in Davies to hear and see the wildly wonderful, powerful performances, look for a good recording. Allow your heart and head to live with this music. SFS has a Beethoven year planned; look at the end of this review for dates.

Beethoven had written a letter to his brothers informing them that he was losing his hearing. While he was experiencing his emotions of the loss, his Second Symphony is joyful. In the first movement, Adagio molto-Allegro con brio, he introduces music with many characters. He abruptly changes into more energy in the Allegro. His letter to his brothers lets them know that Beethoven was forming a new path for his music. This is it. He does not entirely turn his back on the tradition Haydn began, but he now has his own identity. The second movement, the Larghetto, is surprising. It is full of delights. The senses love to be in this atmosphere, and the music stirs up sweetness and sometimes a musical flirtation. There are slow, thoughtful passages, but these moments choose to dance. The third movement, Scherzo: Allegro, is part of Beethoven’s new path. Rather than using the proper Minuet, Beethoven sets a Scherzo which goes faster than a minuet. It brings more character and playfulness as he creates the amazing finale. The Allegro molto takes over. He composes a very long coda. He makes the listener notice that while Beethoven does pay respect to the traditional symphony, now he has his own way of composing. He may set a moment in a form that the audience will understand, but then he writes in his new way. When the symphony ended, I said, “This was fun.” Beautiful and fun.

Symphony No. 7 is made of rhythm rather than music making rhythm. Beethoven finds dramatic rhythms that make excitement. This runs through all the movements. It makes the listeners feel the rhythm in their blood circulating in all the movements. The names of the Symphony No. 7 are something different. Poco sostenuto – Vivace; that means a little sustained, though the music is more than a little sustained. Then, it celebrates in Vivace, lively and cheerful. Allegretto, a little fast just a little less than an Allegro. Presto: very very fast. Allegro con brio: dancing going faster with lively, happy energy. Parts of this symphony were inspired by the marching soldiers. Their triumph over dictatorship was glorious and so was the ending of the symphony. Beethoven uses repetitions of music and especially the rhythms that stamp and march throughout this amazing symphony. The Finale welcomes more and more of the thrilling victories. Beethoven uses lines of an Irish folk-song, “Save Me From the Grave and Wise.” Beethoven makes offbeats jump with the hurrahs of military, folk-dancers winning the challenge.

BEETHOVEN & SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY: The SFS is offering a Beethoven year. So far, SFS conducted by John Storgard, poured their energy and profound playing Symphony #5, January 24, 2026; Yefim Bronfman performed the Appassionata, in his piano recital, Feb., 8; Van Zweden led the SFS in Symphonies #2 and #7, Feb. 19-21; Mao Fujita will play Piano Sonata No.1 in the Shenson Spotlight Series; Feb. 26-27&March 1, SFS conducted by Honeck, presents the Coriolan Overture; in June18, 20-21, SFS, Gaffigan conducts, singers, the SF Chorus, Symphony #9. BE THERE!

Emanuel Ax, pianist

Emanuel Ax, pianist Emanuel Ax and

Emanuel Ax and  Jaap van Zweden, conductor

Jaap van Zweden, conductor

Ludwig van B

Ludwig van B

Cast

Cast

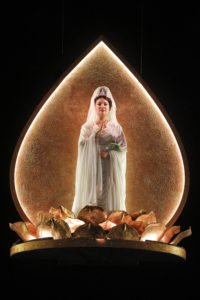

This is the Dragon Palace of the Eastern Sea; making a scene under water is a fabulous event.

This is the Dragon Palace of the Eastern Sea; making a scene under water is a fabulous event. The

The

Itzhak Perlman

Itzhak Perlman