This is the 23rd season of the Music@Menlo, a festival of chamber music and institute for young musicians, Encounters for adults with deep thinking scholars whose talks are entertaining, performances, concerts – just about everything classical music. As an audience member, I began attending their wonderful events in 2003, the first of 23 years of excellence. The founders of the Festival, cellist David Finckel and pianist Wu Han, invented the whole kit-and-kaboodle. Each has stunning talent and expression that places the music somewhere between magic and humanity. Their statement in the season’s program book touches on the magic…” in search of explanations for the miracle of music. This summer is no different, as we focus our lens on a feature of chamber music rarely explored: the magic of chamber music’s rich variety of instrumental combinations, known as ensembles.” This season featured a duo, trios, quartets, a sextet, and an octet.

Johannes Brahms, composer (1833-1897)

Johannes Brahms, composer (1833-1897)

Brahms’ String Sextet no. 1, in B-flat major, op. 18, began an era in which he created several chamber pieces which were warmly received. He had motivation to make chamber pieces. Musicians were going toward Liszt’s tendency to write music that had narrative characteristics. Brahms preferred music which was about music and did not suggest spoken thoughts. He decided that chamber music could be the vehicle to keep music musical. He and his friend, violinist Joseph Joachim, wrote a “manifesto” about two paths for composing. He wrote the String Sextet; he had found the key to more abstract and less programmatic compositions.

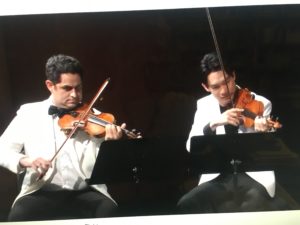

Violinists Arnaud Sussmann, Richard Lin play Brahms’ String Sextet no. 1 in B-flat major, op. 18

Violinists Arnaud Sussmann, Richard Lin play Brahms’ String Sextet no. 1 in B-flat major, op. 18

The six instruments were played by Arnaud Sussmann, Richard Lin, violins; David Finckel, Clive Greensmith, cellos; Tien-Hsin Cindy Wu, Masumi Rostad, violas. The Allegro ma non troppo movement opens with a solo cello backed by the other cello and one viola. The Andante, ma moderato movement is a theme and variation style. Now, the viola moves into the music that had been the cello’s, and the theme comes back in the violin. In the Scherzo: Allegro molto, Brahms uses syncopation. The whole movement moves with rhythmic feats. The listener might begin hearing a “mild” rhythm that then speeds up the tempo. Brahms does not use hemiola, which shows up in other works. The accents in the music make it sound as though music is in twos and threes rhythms simultaneously. The music evolves into a proud and courtly dance that speeds up a lot, as though those proud and courtly dancers had put something in the punch. The Rondo: Poco allegretto e grazioso adopts much of the previous movements. The physical making of music is a visual performance letting loose energy and action. He uses pizzicato from the beginning to the end. The musicians are strumming the instruments. The viola goes faster and faster. The ensemble plucks the strings, and, one instrument at a time, returns to bowing. A fast, innovative, happy finale. It was a greatly satisfying experience created by Brahms and gifted to listeners by the six marvelous musicians.

Jorg Widmann, clarinet, composer (born 1973)

Widmann’s 180 beats per minute was written in 1993. He is quoted in the M@M program book. He said, “I don’t want to repeat myself, I don’t want to get bored with myself. That’s why my pieces are often very different aesthetically.” The variety of time signatures are challenging as he changes them, it seems to me, in every measure. He was experimenting the use of the metronome, and he certainly enjoyed the adventure. He also said that “The work makes no claims to be more than the sum of its parts — the sheer enjoyment of rhythm.” The musicians bringing life to the metronome: Julian Rhee, Kristin Lee, violins; Masumi Rosta, viola; Dmitri Atapine, Nicholas Canellakis, Clive Greensmith ; cellos.

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-1847)

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-1847)

It is difficult to write about Mendelssohn’s Octet. It is an amazing work. I rarely use that word “amazing.” The Taj Mahal. A category 5 tornado. Seeing a bird fly. It is complicated. There are 8 musicians, twice so many as a string quartet, but the instruments play as individual musicians more than as the group or sub-group of violins or violas. Mendelssohn dedicated the work to Eduard Rietz, a violinist, who was the elder brother of Mendelssohn’s friend, cellist Julius Rietz. Eduard became very ill, could not continue his music, and passed away. Felix was sad at this loss, however, the Octet has a brilliant, happy existence. Of course, “Felix” is “happy.” In the Allegro Moderato ma con fuoco, the full ensemble is represented. The viola’s playing is syncopated. A violin takes a ride on a series of arpeggios. The music shakes its feathers and returns to the main theme but makes the transition quietly. There is a mystery. A sad Andante is the second movement. Only occasionally, the Octet moves itself into two separate groups, but there is no earthquake fault line between them. The Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo introduces still another approach. The eight become one playing more quietly together. It could be like a play when everyone is talking. They say peas-and-carrots, peas-and-carrots repeatedly and it comes out sounding like they are sharing gossip or looking for parking. However, there is no narrative here. Every note has been just right. Each of the movements are nothing anyone else has done. This extraordinary, great, great piece closes with a Presto. The cello opens the movement with an extraordinarily difficult passage. The second cellist must move his arms like a quick athlete as the music reflects perpetual motion. It is a thrilling, memorable, happy ending. The cast played out their hearts and rhythms with precision. Wonderful. Violins: Benjamin Beilman, Jessica Lee, Erin Keefe, Julian Rhee. Violas: Masumi Rostad, Tien-Hsin Cindy Wu; Cellos: Nicholas Canellakis, Clive Greensmith.