San Francisco Symphony, Davies Symphony Hall, May 15, 2025 — Dalia Stasevska conducted the SFS through three wildly different pieces; all were played with excellence.

Dalia Stasevska, Conductor, chief conductor of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and artistic director of the International Sibelius Festival.

Dalia Stasevska, Conductor, chief conductor of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and artistic director of the International Sibelius Festival.

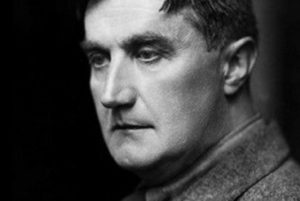

Ralph Vaughn Williams, composer (1872 – 1858), England

Ralph Vaughn Williams, composer (1872 – 1858), England

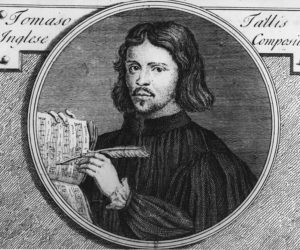

Ralph Vaughn Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis opened the concert. Tallis ( ca.1505- 1585) was a 16th century composer. He provided music for three kings and one queen; starting with Henry VIII and ending with Queen Elizabeth I.

Thomas Tallis, composer (ca. 1505 – 1585), England) Ralph Vaughn Williams spent two years editing the English Hymnal. This turned his ear to the fine, sacred music of earlier times, and it influenced what he came to write. The music is delicate but still strong. In one part, it creates a sound like that of an ancient cathedral. It is only strings. Vaughn Williams divided the strings into differently sized groups. The music could be called “otherworldly.” It has the beauty we will never know except in this music. Thinking back to the 16th century, how can we do that. Thinking back to 1910 when it was composed, also another world. We are so fortunate to hear this and imagine.

Thomas Tallis, composer (ca. 1505 – 1585), England) Ralph Vaughn Williams spent two years editing the English Hymnal. This turned his ear to the fine, sacred music of earlier times, and it influenced what he came to write. The music is delicate but still strong. In one part, it creates a sound like that of an ancient cathedral. It is only strings. Vaughn Williams divided the strings into differently sized groups. The music could be called “otherworldly.” It has the beauty we will never know except in this music. Thinking back to the 16th century, how can we do that. Thinking back to 1910 when it was composed, also another world. We are so fortunate to hear this and imagine.

Anna Thorvaldsdottir, composer (Born 1977, in Iceland)

Anna Thorvaldsdottir, composer (Born 1977, in Iceland)

Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s Before we fall featured the cellist soloist, Johannes Moser. This was a world premiere of this SF Symphony commission. The title suggests the moments before the earth’s ecosystem collapses forever. The composer offers this explanation of her “core inspiration behind the cello concerto Before we fall centers around the notion of teetering on the edge, of balancing on the verge of a multitude of opposites. The musical structure flows between lyricism and a sense of distorted energy–two main forces that stabilize this entropic pull. Driven by the strong sense of lyricism that permeates the piece, the work also orbits a forward-moving energy that connects and balances the opposites in different ways.” The music was powerful and mysterious. There were novel ways of making music and putting the music into the rhythms. There were sticks hitting sticks making new music. The cellist worked strenuously, pressing the moments forward and sometimes pulling back. For this listener, it felt very cold although the sounds could become lyrical. The music is continual, not in movements and without a sense of finality; instead, we are surely balancing against forces beyond our time.

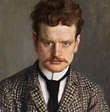

Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957), Finland

Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957), Finland

Jean Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Opus 82 closed the concert with astounding brilliance. What experiences there are in this great symphony! Sibelius was aiming at completing this symphony in time for his birthday. World War I had just begun as he began writing and revising the symphony. It was done in 1919 with the European world back to what would have to pass for stability and peace, for a while. When beginning his 5th, in 1914, Sibelius wrote “In a deep valley again. But I already begin to see dimly the mountain that I shall ascend….God opens His door for a moment and His orchestra plays the Fifth Symphony.” It opens with E-flat major which puts it into the company of Beethoven’s Eroica and the Emperor Concerto, all opening with an E-flat major chord, but this E-flat major belongs to Sibelius. He uses many diverse approaches: chords in crescendo, flutes and oboes, woodwinds blowing through. The audience sits up as the music gives nothing less than surprise; we must react. His rhythms cross over, a dance sings with rhythm, the brass introduces a scherzo, the orchestra repeats a call. Sibelius originally had four movements in the 5th, but changed it into three movements. His second movement has new sounds for rhythms; some are energetic, others are more calming. What will happen to those rhythmic themes? The finale movement takes off like a tornado whirling through space. Sibelius gives the audience amazing excitement, a lift off of woodwinds and cellos, dissonance, new melodies. There is such a rush that the final four chords make the eyes open wider. It is done, and we want to start again.

The conductor, Dalia Stasevska, was a star throughout the concert, and yet her physicality and attention was especially fantastic in this Sibelius masterpiece. The SFS rose to play on an even higher level – we thought they were already up there – and entirely with her in this great Symphony No. 5. Orchestra and Maestro were were thrilling.

The conductor, Dalia Stasevska, was a star throughout the concert, and yet her physicality and attention was especially fantastic in this Sibelius masterpiece. The SFS rose to play on an even higher level – we thought they were already up there – and entirely with her in this great Symphony No. 5. Orchestra and Maestro were were thrilling.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Sympony, conducts the All Sibelius program, March q4, 2024

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Sympony, conducts the All Sibelius program, March q4, 2024

Joshua Bell

Joshua Bell

Jorg Widmann, composer, conductor, clarinetist

Jorg Widmann, composer, conductor, clarinetist

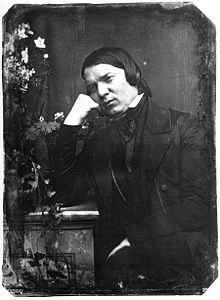

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

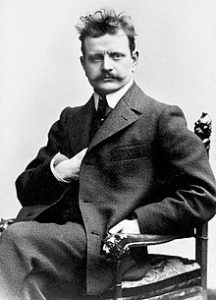

Jean Sibelius, 1913

Jean Sibelius, 1913

Daniil Trifonov (photo by JKruk)

Daniil Trifonov (photo by JKruk)