The exciting exhibition, Truth & Beauty, at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor Museum casts an aura around visitors with its romance and jewel-like colors. It opened on June 30 and closes on September 20. Visiting the works of English artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) , Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and of the artists of the Northern and Italian Renaissance, Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, ca. 1483-1520), Sandro Botticelli (ca.1444/1445-1510), Jan Van Eyck (ca. 1390-1441), gives the viewer sensual delights, an understanding of the inspirations of artists, and an appreciation of a generation’s efforts to throw off conventional ways and create something of its own.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed by a group of young artists, men and women, in mid-nineteenth century England. They were consciously establishing a new aesthetic and defined their goals for all to know: “1 To have genuine ideas to express; 2 to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them; 3 to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote; and 4 and most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.” They had unusual opportunities to view great art from early times. Prince Albert (Queen Victoria’s husband) was a devoted collector of early German and Netherlandish paintings and helped organize an exhibition, “Art Treasures,” in Manchester, 1857. It showed early masters of Netherlandish and German art. In 1848, the British Institution, London, showed an exhibition of paintings from early Italian artists from “the times of Giotto and Van Eyck.” These exhibitions, even when including “misattributed” works awakened English artists to fourteenth and fifteenth century accomplishments.

Visitor to the exhibtion views work(left) by Fra Angelico (ca.1400-1455) (copy of The Annunciation), and (right) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giotto Painting the Portrait of Dante (1852) The early artists like Giotto (ca.1267-1337) in Italy or Jan Van Eyck in the Netherlands had been given credit primarily for inspiring the generation of Michaelangelo rather than for their own revolutionary vision. This included their use of perspective, Giotto’s representation of humans who looked like ordinary humans, the golden boards of the late thirteen century into fourteenth century paintings. Giovanni Villani wrote that Giotto was the foremost painter of his time and “drew all his figures and their postures according to Nature.”

Visitor to the exhibtion views work(left) by Fra Angelico (ca.1400-1455) (copy of The Annunciation), and (right) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giotto Painting the Portrait of Dante (1852) The early artists like Giotto (ca.1267-1337) in Italy or Jan Van Eyck in the Netherlands had been given credit primarily for inspiring the generation of Michaelangelo rather than for their own revolutionary vision. This included their use of perspective, Giotto’s representation of humans who looked like ordinary humans, the golden boards of the late thirteen century into fourteenth century paintings. Giovanni Villani wrote that Giotto was the foremost painter of his time and “drew all his figures and their postures according to Nature.”

The Pre-Raphaelites did not ignore the beauties of the Renaissance. In fact, in the literary and visual art sources of their inspiration as well as their personal ways of dressing or hair styles, they assimilated their interpretation of medieval values, working them into their modern, mid to late nineteenth century outlook.

(Left) Raphael self-portrait; (Right) Sandro Botticelli (near left) Idealized Portrait of a Lady (ca. 1475)

(Left) Raphael self-portrait; (Right) Sandro Botticelli (near left) Idealized Portrait of a Lady (ca. 1475)

In Beata Beatrix, Beatrix seems to experience a moment of ecstasy while Dante, in his red cloak, is pictured at a distance behind her. Dante, his love and life stories, figured prominently among the literary inspirations for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Ideas about medieval chivalry and heroic love were celebrated in their paintings and also in poetry and prose by William Morris (1834-1896), a “second generation” Pre-Raphaelite, and Christina Rossetti (1830-1894), Dante Gabriel’s sister. In addition to his writings, left wing politics, and business successes, Morris focused on designs derived from nature. The close observation of nature, a Pre-Raphaelite tenet, shows up in the lovingly, accurately drawn plants in so many paintings as well as Morris’ repeating vines and leaves made for wall papers and furnishings.

Renewed interest in the Pre-Raphaelites’ art and their personal histories quickened during the late 1960s-early 1970s. A person in her twenties could be moved by the Pre-Raphaelites: William Morris’ idea that everything from spoons to tables in a cottage or a castle should be made with art as well as his imaginative and revolutionary writing; Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s shoulder length hair (and his lamentable, tragic drug use); their unconventional love lives; the deep, shining colors of their paintings; their close attention to nature. There was the revival of medieval styles in clothing: homespun looking shirts with wooden buttons and wide, loose sleeves for men; floor length skirts for women; long hair for everyone. Some aspects of these trends were superficial and some were approached with attention to deeper significance. A longing to “go back to nature” may not be so greatly in the news, but its offspring, the longing to save what’s left of nature goes on.

(Rt) Veronica Veronese (1872), by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Her left hand plucks a violin. Her right hand rests near a daffodil; a circle of daffodils is below her desk. A leafy vine hangs from a bird cage in the upper left, behind her. For further information see: legionofhonor.org/truth-and-beauty Museum hours: 9:30 a.m.-5:15 pm, Tuesday – Sunday

(Rt) Veronica Veronese (1872), by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Her left hand plucks a violin. Her right hand rests near a daffodil; a circle of daffodils is below her desk. A leafy vine hangs from a bird cage in the upper left, behind her. For further information see: legionofhonor.org/truth-and-beauty Museum hours: 9:30 a.m.-5:15 pm, Tuesday – Sunday

PHOTOS: All photographs by Jonathan Clark, Mountain View, CA The title of the exhibition comes from Ode On a Grecian Urn, by John Keats, an English Romantic poet who was also inspired by ideas of the medieval times.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Director, Max Hollein standing next to The Lady of Shalott, painting (circa 1888 – 1905) by William Holman Hunt. Director Hollein appeared 6/28, his last day as Director before he left to become Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the very next day.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Director, Max Hollein standing next to The Lady of Shalott, painting (circa 1888 – 1905) by William Holman Hunt. Director Hollein appeared 6/28, his last day as Director before he left to become Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the very next day.  (Left) Beata Beatrix (1871/1872) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti; (Right) A Crowned Virgin Martyr (Saint Catherine of Alexandria) by Bernardo Daddi (ca.1280-1348)

(Left) Beata Beatrix (1871/1872) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti; (Right) A Crowned Virgin Martyr (Saint Catherine of Alexandria) by Bernardo Daddi (ca.1280-1348)  (far Lt) Flora; (near Rt) Pomona, by Edward Burne-Jones; (low Ctr) Bayes Chest, by Jessie Bayes (1878-1971) assisted by Emmeline Bayes (1867-1957) and Kathleen Figgis. The chest (ca. 1910) is decorated with pictures and quotes from La Morte d’Arthur, by Sir Thomas Malory. The story of King Arthur’s death and interest in the Arthurian legends (or history), combined tales of romance and chivalry that inspired the Pre-Raphaelites.

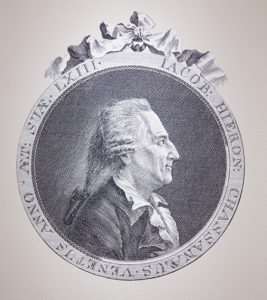

(far Lt) Flora; (near Rt) Pomona, by Edward Burne-Jones; (low Ctr) Bayes Chest, by Jessie Bayes (1878-1971) assisted by Emmeline Bayes (1867-1957) and Kathleen Figgis. The chest (ca. 1910) is decorated with pictures and quotes from La Morte d’Arthur, by Sir Thomas Malory. The story of King Arthur’s death and interest in the Arthurian legends (or history), combined tales of romance and chivalry that inspired the Pre-Raphaelites. Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798)

Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798)

(Left) Franceso Guardi (Italian, 1712-1793) The Ridotto of Palazzo Dandolo at San Moise with Masked Figures Conversing ca. 1750. The ridotti were state sponsored gambling rooms, sometimes places of music and dancing. Everyone was required to wear masks which made it easier for thieves and prostitutes to mix with the elite. (Right) 18th c. Sedan chair which belonged to Alma Spreckles, founder of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor

(Left) Franceso Guardi (Italian, 1712-1793) The Ridotto of Palazzo Dandolo at San Moise with Masked Figures Conversing ca. 1750. The ridotti were state sponsored gambling rooms, sometimes places of music and dancing. Everyone was required to wear masks which made it easier for thieves and prostitutes to mix with the elite. (Right) 18th c. Sedan chair which belonged to Alma Spreckles, founder of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor

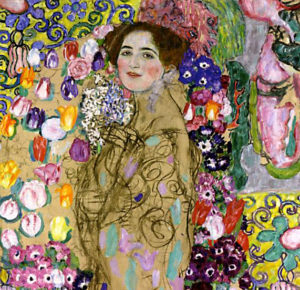

(Left)

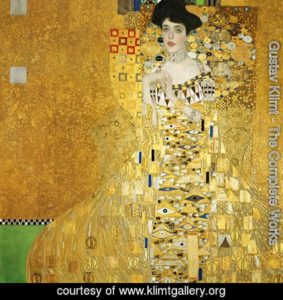

(Left)  Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) (not part of this exhibition)

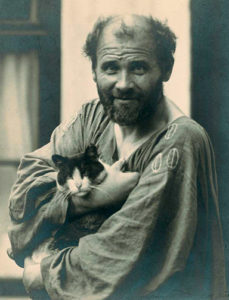

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) (not part of this exhibition) Gustav Klimt and his Cat (Katze), photo by Moritz Nahr

Gustav Klimt and his Cat (Katze), photo by Moritz Nahr

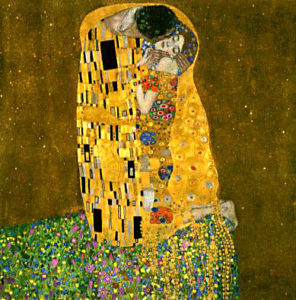

Klimt, The Virgin, 1913

Klimt, The Virgin, 1913 Edgar Degas, The Millinery Shop, 1879-1886, Art Institute of Chicago.

Edgar Degas, The Millinery Shop, 1879-1886, Art Institute of Chicago. Edouard Manet, At the Milliner’s, 1881, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Edouard Manet, At the Milliner’s, 1881, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Edgar Degas, The Milliners, ca.1898, Saint Louis Art Museum

Edgar Degas, The Milliners, ca.1898, Saint Louis Art Museum

ALL PHOTOS ©JONATHAN CLARK.

ALL PHOTOS ©JONATHAN CLARK.