On June 22, the Hedgehogs were in the audience for the powerful performance of Prokofiev’s Concerto No. 2 in G minor for Piano, Opus 16. It was a privilege to be there. Yefim Bronfman, the pianist, is surely one of the greatest pianists. His mastery of this Concerto reveals his mastery of Prokofiev’s music and of the art of the piano. Prokofiev’s Concerto No. 2 is demanding on every level: technique, emotion, physical abilities. Bronfman triumphs

in every category with magnificent partnership of the SF Symphony. Bronfman made the challenges of playing this grand, gorgeous, overwhelming music seem to come to him naturally. He breathes the music and the Davies Symphony Hall audience was captivated as he led them on an enormous journey. Mr. Bronfman will continue touring through the US and abroad this summer. If you are anywhere near one of his concerts, go. Do not miss his performances. Everyone who loves music will talk about the experience forever.

The composer, Sergei Prokofiev, found this concerto’s piano solo difficult to play. It is said that he complained of how hard it was for him to learn and perform. Prokofiev won first prize in piano from the St. Petersburg Conservatory so his opinion of playing his creation must be accepted. The Concerto No. 2 is the second in more than one way. His first composition of it was lost in a fire, in 1918. Not yet published, the concerto was lost. Prokofiev had fled the revolution in Russia and gone to Paris. In 1923-1924, he reconstructed it from notes and added new music. The concerto is melodic, suggests dances, machine sounds, and, in the third movement, even sounds threatening. Throughout, the meter changes grabbing the audience’s attention to a piano that is played almost faster than one can listen. It is a giant, life journey.

Yefim Bronfman was born in Tashkent, in Central Asia, a former part of the Soviet Union. He and his family immigrated to Israel where he studied piano with Arie Vardi, head of the Rubin Academy of Music, Tel Aviv University. Moving to the US, he studied at the Juilliard and Marlboro Schools of Music and at the Curtis Institute of Music. His teachers were Rudolf Firkusny, Leon Fleisher, and Rudolf Serkin. He became an American citizen, in 1989. Among his honors: he won the Avery Fisher Prize, 1991. He has been nominated for 6 Grammy Awards and won in 1997 for a recording of the three Bartok piano concertos with Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Yefim Bronfman was born in Tashkent, in Central Asia, a former part of the Soviet Union. He and his family immigrated to Israel where he studied piano with Arie Vardi, head of the Rubin Academy of Music, Tel Aviv University. Moving to the US, he studied at the Juilliard and Marlboro Schools of Music and at the Curtis Institute of Music. His teachers were Rudolf Firkusny, Leon Fleisher, and Rudolf Serkin. He became an American citizen, in 1989. Among his honors: he won the Avery Fisher Prize, 1991. He has been nominated for 6 Grammy Awards and won in 1997 for a recording of the three Bartok piano concertos with Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Also on this program were Fratres for Strings and Percussion by Arvo Part, Music for Ensemble and Orchestra by Steve Reich, and Polovtsian Dances by Alexander Borodin.

The SF Symphony’s performance of the Polovtsian Dances was beautiful as the SFS captured the exquisite, dancing music and enchanting, exotic folkoric sounds. Just when the listener comes close to being lulled into a dream, the 12th century military campaign of Prince Igor against the Polovtsian tribe re-enters with force and passion. Bravo, Borodin!

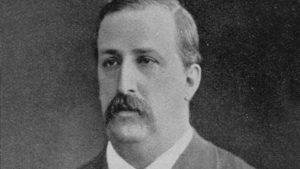

Yefim Bronfman

Yefim Bronfman Alexander Borodin

Alexander Borodin

pictures: above, Yefim Bronfman; L-Rt, Brahms, Berg

pictures: above, Yefim Bronfman; L-Rt, Brahms, Berg