Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, March 30 — This was a great program. Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 77 and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Opus 93.

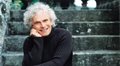

If you ever learn that Gil Shaham, violinist, is playing near you, someplace on this same planet, go to hear and see him. He was the guest soloist playing Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D major. He is a blissful musician and shares the bliss with his audience. As he played, he related to the conductor, Juraj Valcuha, and also turned toward the Concertmaster, Alexander (Sasha) Barantschik. It seemed that he wanted their experiences in the music to fit with each other so that they enjoyed making music together.

Gil Shaham, violinist, He performs regularly with the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Israel Philharmonic. He has multi-year residencies with Montreal Symphony, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Singapore Symphony.

Gil Shaham, violinist, He performs regularly with the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Israel Philharmonic. He has multi-year residencies with Montreal Symphony, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Singapore Symphony.

The Concerto is something different in Brahms’ repertoire and new to the late19th century audience for serious music. “Normally,” in concerti of the era, the orchestra was a frame for the music made by the soloist. The soloist dominated the two-some. In this concerto, they are equals. It also offers new, off-center rhythms that made the listeners at the 1879 premiere decide it was a strange Brahms, as though he had heard wisps of this music from E.T. The first movement has a lovely, lyrical method to carry through changes from major to minor and the presence of Hungarian folk tunes folded into this Allegro non troppo. I remember it, even when there are surprising switches, as a deep and moving quiet, moving like a river, not entirely moving like an emotion. This is where an Adagio oboe melody drifts through gentle but never weak, winds. The violin brings more musical strife and then it all becomes calm, but never still. The finale, Allegro giocoso ma non troppo (happy but not too happy) is obviously demanding over-the-top technical brilliance. Shaham was in clover. It was not a bit challenging to him as the full audience were thrilled.

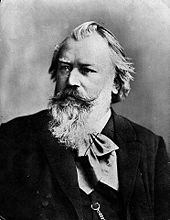

Johannes Brahms, composer (1833-1897) This is the first Violin Concerto he wrote. He was pounced on by writers and music lovers. What had he done? He had made a great piece with new sounds and rhythms which were not welcomed. The reception rattled him so much that he destroyed his second violin concerto and never wrote another. Occasionally, I hear the finale movement of the Violin Concerto in D major on the radio, but not the whole concerto. It is a rare jewel. Shaham, Valcuha, and the SF Symphony gave it the performance it deserves.

Johannes Brahms, composer (1833-1897) This is the first Violin Concerto he wrote. He was pounced on by writers and music lovers. What had he done? He had made a great piece with new sounds and rhythms which were not welcomed. The reception rattled him so much that he destroyed his second violin concerto and never wrote another. Occasionally, I hear the finale movement of the Violin Concerto in D major on the radio, but not the whole concerto. It is a rare jewel. Shaham, Valcuha, and the SF Symphony gave it the performance it deserves.

Dmitri Shostakovich, composer (1906-1975)

Dmitri Shostakovich, composer (1906-1975)

On one of my first visits to the San Francisco Symphony, I learned that they would not play anything by Shostakovich. It shocked me. The idea was that Shostakovich was a loyal Russian Communist, and therefore an enemy. Later, Leonard Slatkin was a guest conductor. He spoke to the audience and encouraged them to understand Shostakovich’s hunted life, and appreciate the greatness of his music. It surprises me now to note that some music writers still assume that Shostakovich was all about Communism and writing music that supported the current ideals. Some even treat the two times he had lost approval by Stalin’s regime was, “after all, only twice.” This is a great composer. He could not have his work performed. He could not work. He wrote for movies, and tried to be rehabilitated. He had to know that other artists had been sent to Siberia, which was a place to die, or, they were shot. When he was allowed to go to the US as an artist on display but with grim chaperones, he was reported to look like a prisoner speaking what he had to say. He was denounced by the authorities, lost his teaching positions, did not write between his Symphony No. 9, 1945, until the Symphony No. 10, 1953. What happened? Stalin died. So, the question about his Symphony No.10 in E minor, Opus 93 is whether the Symphony was specifically about Stalin. For myself, I think it is about Stalin, but not as a portrait of that dictator. The atmosphere, what there was to breathe, what to think, how not to think was all Stalin and his cohorts all the time. Shostakovich and other artists who lived in Stalin’s world had lives which were continually repressed by the entire regime. Shostakovich was there; his family and private life were constantly in danger.

The Symphony opens with the cellos and basses. Moderato, it has a sound lying under the music; that sound says, “Be careful. You may be watched.” The strings carry the movement forward to language from solo instruments: a clarinet solo, a horn fills the music, more clarinet, and a flute accompanying plucking strings. The whole orchestra builds its very loud cries, and the music becomes even louder. Briefly, it sounds like an army. The movement ends with piccolo and timpani. The listener, becoming anxious, catches her breath, but still the eyes open wide in the quiet but ghostly end. The second movement is an Allegro, like a super fast scherzo. It is rushing to the edge of the moon. Is someone running away? Is a whole nation running after…what? It pushes the heart of the music. There is no moment to think; the strings play very, very quietly. The scherzo abruptly cuts itself off. The third movement has three styles: Allegretto – Lento – Allegretto. It is not so fast as the Allegro, but runs briskly. Then, there are slower moments and a return to the brisk movement. There is a teasing, lively mood that has that under lying, troubling, secret sound. The piccolo, flute, timpani, and triangle present a sardonic tone as the music marches on. The Symphony ends with Andante – Allegro beginning similarly to the first movement’s cellos and basses. A lovely oboe almost calms the music as once again the flute flies solo. Now, the wildness of the second movement becomes an energetic, klezmer. It is at last a joyful sound for all of us.

Shostakovich at the piano

Shostakovich at the piano

Anton Nel, pianist

Anton Nel, pianist Peter Wyr

Peter Wyr

Cecile Chaminade, composer, pianist (1857 – 1944)

Cecile Chaminade, composer, pianist (1857 – 1944) Johannes Brahms, composer (1833

Johannes Brahms, composer (1833

Opera sing

Opera sing

Jean-Ives Thibaudet

Jean-Ives Thibaudet

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)